|

| A photograph of the train station (foreground, right) in St. Paul, Alberta; year unknown; taken by Ron Brown, and published in the 3rd Edition of The Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore: An Illustrated History of Railway Stations in Canada (Toronto: Dundurn Group, 2008): p. 41.NOTE: This post was originally featured in my non-academic blog 'The Organic Intellectual', on February 16th, 2011. |

Sometimes, ordinary photographs have an uncanny ability to capture our attention. This one (above) captured mine. I was leafing through Ron Brown's The Train Doesn't Stop Here Anymore: An Illustrated History of Railway Stations in Canada, and came across this image, and my brain stumbled upon the caption: "The station skyline in St. Paul, Alberta, is typically dominated by the grain elevators. Photo by author." Grain elevators and a train station in St. Paul, Alberta!? I have been to St. Paul many times, yet I have never seen any grain elevators there. Nor had I ever seen or heard of a train station in town - this would imply passenger service. But here was a photograph of a typical prairie town, showcased in a book about abandoned train stations, chosen specifically because of its iconic prairie 'skyline' - dotted with not just one, but five of the multistory beasts! Was it possible that, despite the dozens of visits to the town, I had never come across the rail station and somehow failed to see the town's tallest edifices? Surely, a story was hiding behind this photograph, so I have spent some time trying to brush off some of the dust.

St. Paul, located about 200km Northeast of Edmonton, was settled by the Oblate missionaries in the late 19th Century as a mission for Métis peoples. The settlement was originally known as St. Paul des Métis (shortened to St. Paul in 1936, when the settlement gained 'village' status). In 1909 the settlement was opened up after the original mission project was abandoned, and the doors were opened for French-speaking families from throughout the region and Québec, as well as other European settlers (mostly from Ukraine and the United Kingdom) to move in and break ground. However, like many prairie locales, it was the arrival of the railway that really facilitated the growth of St. Paul into a town...

In the early decades of the 20th Century, even getting between Edmonton and St. Paul was a struggle. From St. Paul, one had to travel some 105 kilometers by horse and buggy to Vegreville, where one of the oldest railway lines in the province was situated, owned at the time by Canadian Northern Railways (CNoR). CNoR was started in 1895 in an attempt to compete with Canadian Pacific Railways (CPR) - the company started building track in Manitoba and thereafter spread its network East and West. By 1905, CNoR tracks had reached Edmonton through a southern route (see Figure 1), offering an alternative to the CP's route. In 1914, CNoR began construction of a more Northern route to Saskatchewan, but as the Alberta Heritage Community Foundation notes, the war effort stalled progress:

"... railroad officials claimed there was a shortage of labour, and construction stopped at Spedden in 1919, 48 kilometres short of St. Paul. As did many communities on the Canadian Prairies, they banded together, and recognizing the importance of the railway to the town’s economic prosperity, the citizens of St. Paul volunteered to complete the last stretch of track that would join their town with North Edmonton. In 1920, the first regular service train arrived in St. Paul. J.A. Fortier was the first Station Master and lived with his family in the station building, which was to become an important economic and service centre. Trains not only allowed passenger travel, they also brought mail, equipment, and merchandise. The railway also meant farmers could transport cattle and crops to larger urban centres more easily."

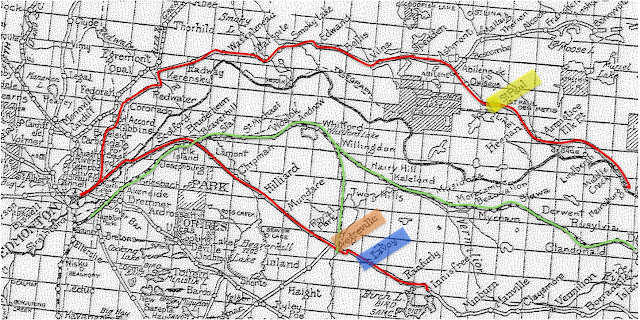

Figure 1: Map of Alberta Railways, from the Waghorn Guide, 1941

By 1918, CNoR and other railway companies were consolidated into the

new crown corporation, Canadian National (CN). The roaring twenties

were a time of prosperity in Northeastern Alberta.At the time, CN and CP

rail lines criss-crossed the countryside like the arteries of the

nation. Indeed, the growth of the railway network deeper into Canadian

territory facilitated the growth of the nation long into the second

half of the 20th Century. As Tom Murray's Rails Across Canada

notes, "in the decades after the [Second World] war, Canada became a

supplier of resources to the world - lumber, grain, sulfur, potash,

petroleum products - and CN [and CP] carried them."

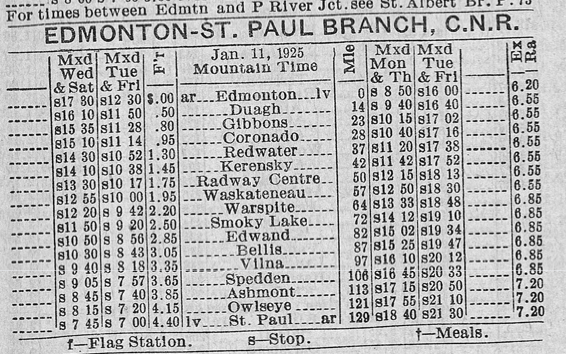

The

first half of the 20th Century is perhaps the heyday of Canadian

passenger rail service. With automobiles and fossil fuels still largely

commodities of the elite, trains were a necessary aspect of keeping

people and communities connected. The train line between Edmonton and

St. Paul, which the community members had helped to complete, was by no

means quick (see Figure 2), but it was nevertheless reliable and,

arguably, the common person's primary connection to the outside world.

In 1946, the train was upgraded to daily service, and was by then fast

enough to allow those from small lineside communities such as Bonnyville

to come to the service town of St. Paul for the day, and make it back

home in time for early evening.

Figure 2: Passenger Rail schedule from Edmonton to St. Paul, 1925

|

| The schedule, from the 1925 Waghorn Guide, tells us that four return trips per week connected St. Paul and Edmonton. The train took an astonishing 10 hours to traverse 200 kilometers! |

Vehicular Homicide: Killing Passenger Rail

The 1950s and

1960s marks a dramatic decrease in rail passenger demand (and supply of

services) in North America, notably correlating with the post-war boom

and the rise of the family automobile as the primary means of mobility.

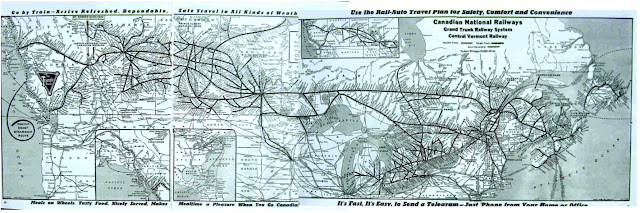

With each successive decade from the 1920s to present, a map of Canada's

passenger rail service would get thinner and thinner (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Canadian Passenger Rail in the 1920s and 2000s compared

Figure 4: No more prairie skyline

The passenger rail service between St. Paul and Edmonton continued to

be offered by CN into the early 1970s, but it was then quietly

discontinued; the age of cheap oil had facilitated the rise of the

automobile - and today the automobile is the only functional means for

people to get in or out of St. Paul (aside from the Greyhound bus, which

travels twice a day).

From Tracks to Trucks

For

the meantime, freight services would take over as the main function of

the St. Paul railway. As Brown's photograph attests, freight played an

extremely important role in this largely agricultural region's economy.

It is only after speaking with my partner's uncle Wayne, a longtime

farmer from St. Paul, that I have come to begin to understand the

centrality of the freight rail service (and the corresponding grain

elevators) to the rural way of life: First, the rail service provided an

efficient and cheaper way of bringing important farm inputs, ranging

from fertilizers to heavy equipment, to the region. Second, the local

grain elevators (and the agglomerations of farmers who owned them)

provided local farmers with a sense of ownership and control over their

product. They had a say in the local wheat pools, or at least knew who

was serving on the regional board, and could make important decisions

about their produce based on the buyer, the going price, and it's final

destination (farmers like Wayne were even involved in loading their own

rail cars with their own goods, for which they were paid a higher share

of the product). Third, the elevators served as a rallying/ meeting

point for local farmers. As Wayne put it: "We would come together and

meet there, share ideas, discuss and network with other farmers." But as

the past tense tone used here suggests, these important socio-economic

functions of the regional freight railroad (and the grain elevators) are

no longer available... they are no longer available because, within the

last two decades, CN began to discontinue its freight services in parts

of the region. Today, the evidence of a former era has been removed:

The grain elevators have been torn down; the rails have been ripped out.

Covering Their Tracks

Now,

it's one thing to discontinue passenger and freight rail service; it's

quite another to rip out the tracks and dismantle the infrastructure!

But this is precisely what would eventually happen in St. Paul, in a

decision that Wayne describes as "beyond shortsighted". Today, the

iconic prairie image captured by Brown's photograph is completely

obliterated in St. Paul and many small agricultural towns like it. The

previous landscape has literally been erased: The rails have been

removed, buildings torn town, and power lines replaced (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: No more prairie skyline

How did this happen? Well, there are a myriad of reasons and forces

which have come into play, some of which I will briefly touch on here.

In some ways, the death of Brown's photograph is a parable of the local

impacts of globalization. As mentioned above, the 1960s and 1970s saw

the growth of automobile-based infrastructure. Similarly, by the 1980s,

freight companies such as CP and CN began to feel competing pressure

from the trucking industry. The rail companies began to discontinue

service in more remote areas, in order to cut back on losses to the

trucking companies.

The privatization of CN in 1995

didn't help either. Thereafter, CN began looking into ways of downsizing

services and increasing profit margins. In 1993, as CN eyed its future

fate as a private corporation requiring new sources of finance capital,

it put up secondary lines like the St. Paul rail corridor for sale. The

idea was to keep servicing the area, but to raise funds by selling the

valuable property to municipal stakeholders. The corridor was purchased

by the County of St. Paul. Nevertheless, thanks to heavy lobbying

efforts by recreational snowmobile and all-terrain vehicle (ATV) groups,

a plan was floated to consider turning the corridor into a 'linear

park', a trail to be used for such recreational purposes. Meanwhile, the

trains kept coming to St. Paul, collecting agricultural products and

delivering various goods.

The final death-knell came in

1999, when CN announced it would abandon rail service in Northeastern

Alberta. Two years later, the county held a referendum on the following

question: "Do you support a municipally-regulated public trail on the

soon to be abandoned CN railway right of way?" Three affected rural

municipalities voted on the resolution, and a slight majority voted in

favor - totaling the "Yes" vote to 54.1%. There was no legal requirement

to obtain anything more than a simple majority, and thus the

recreational park - later to be ironically dubbed the "Iron Horse

Trail", began to be constructed shortly thereafter. Today, the trail is

marketed as a tourist destination.

In St. Paul, the

rails were removed and oddly, the grain elevators and historic station

building were demolished (forget heritage status!). For Wayne, the

decision to rid of the grain elevators was symbolic, and could be

interpreted more sinisterly as a way to pit farmers against one another

and consolidate the control of large multinational grain companies.

Today, small-scale farmers do not have it easy - they are likely the

ones who have lost the most from the disappearing railways and grain

elevators. They have to arrange (and pay for) their own private

transport of such inputs and their own agricultural output (by truck).

Bringing in heavy equipment is extremely difficult and costly. Rather

than have a say in coordinating the flow of their product with fellow

collaborators at the regional wheat pools, they are all too often "told

what to do" by the companies who own farmer's debts. This is the focus

of Ingeborg Boyens' Another Seasons Promise. As one review of Boyens' book notes:

Another Season's Promise explores the farm crisis not as a series of occasional individual losses caused by poor growing seasons, but rather as a perpetual structural phenomenon composed of many villains. Family farmers face down multinational agribusiness, pressure to grow genetically modified foods, the perils of factory farming, massive dependence on pesticides, and an increasingly distant federal government more interested in pleasing international trade bodies than supporting Canadian farmers.

The

loss of the local elevators and railroad have played a small (but

significant) role in this complicated process... but ironically, the way

out of this mess would be much facilitated by the very infrastructure

which helped build such farming communities in the first place. We must

recognize that these hardships are being experienced in an era of

relatively cheap oil. What will happen when the price of inputs and

shipping skyrockets as a result of a higher oil prices? What will

happen when we decide to take climate change seriously, and enact

policies that limit the amount of fossil fuel use? How are small rural

Canadian towns like St. Paul going to facilitate the mobility of people

and goods when fossil fuel based automobiles and trucks are no longer a

viable mode of transportation? It is thus clear why a local farmer and

longtime community member like Wayne would see the dismantling of the

rail infrastructure as shortsighted. This is not to suggest that a

recreation trail is a bad thing (quite the contrary, publicly-owned

recreation areas, and people coming together to have fun and be healthy

is a good way to build community). The shortsighted aspect is that the

replacement of rails and agricultural buildings clearly does not take

into consideration the long-term community implications of losing such

crucial infrastructure - the type of infrastructure that has played a

pivotal role in the foundation of rural life in Canada.

No comments:

Post a Comment